Hurricane Beryl: How did Jamaica’s DRF strategy stack up?

Hurricane Beryl

How did Jamaica’s DRF strategy stack up?

Author: Conor Meenan

Credit: Chandan Khanna/AFP via Getty Images

Credit: Chandan Khanna/AFP via Getty Images

Hurricane Beryl in July 2024 presented an early test in the season for Jamaica’s disaster preparedness. The eye of the storm passed to the south of the island, but strong winds and flooding in southern coastal areas caused an estimated damage and loss of 1.1% of Jamaica’s GDP. Multiple instruments in the country’s US$1.6 billion disaster risk financing (DRF) strategy activated. Following the storm, there was criticism of Jamaica’s catastrophe bond which had narrowly avoided a US$45-million payout. However, a deeper analysis of Beryl’s impacts and Jamaica’s DRF strategy uncovers a more positive picture about how pre-arranged financing can help manage climate shocks.

This long-read aims to build a clearer picture of Beryl’s impacts and Jamaica’s financing response by addressing three questions:

- How much did Beryl cost the Government of Jamaica?

- How did instruments in Jamaica's DRF strategy respond?

- Should Jamaica’s catastrophe bond have triggered?

On the surface, questions like this appear simple, but crisis events are often complex, and the full picture of actual losses and the technical details of pre-arranged financing instruments are not always readily available. The analysis in this blog seeks to navigate this challenge by consolidating publicly available information. It draws conclusions about what worked well for Jamaica and what other countries can learn from their approach.

How much did Beryl cost the Government of Jamaica?

Credit: Scott McIntyre/Bloomberg via Getty Images

Credit: Scott McIntyre/Bloomberg via Getty Images

Jamaica’s planning institute (PIOJ) has a strong record of analysing and publishing detailed breakdowns of disaster-related losses and damages, experienced across sectors and between public and private risk holders. The detailed assessment of Beryl’s damages and loss is not yet available, but other public sources help refine the range of potential costs to Jamaica’s government:

Total economic loss and damage for Beryl is estimated at approximately US$200 million, or 1.1% of GDP. This high-level estimate was shared in a mid-year review of economic performance. It includes damages to publicly owned and managed infrastructure, but also costs to affected households and lost revenue from private businesses and productive sectors.

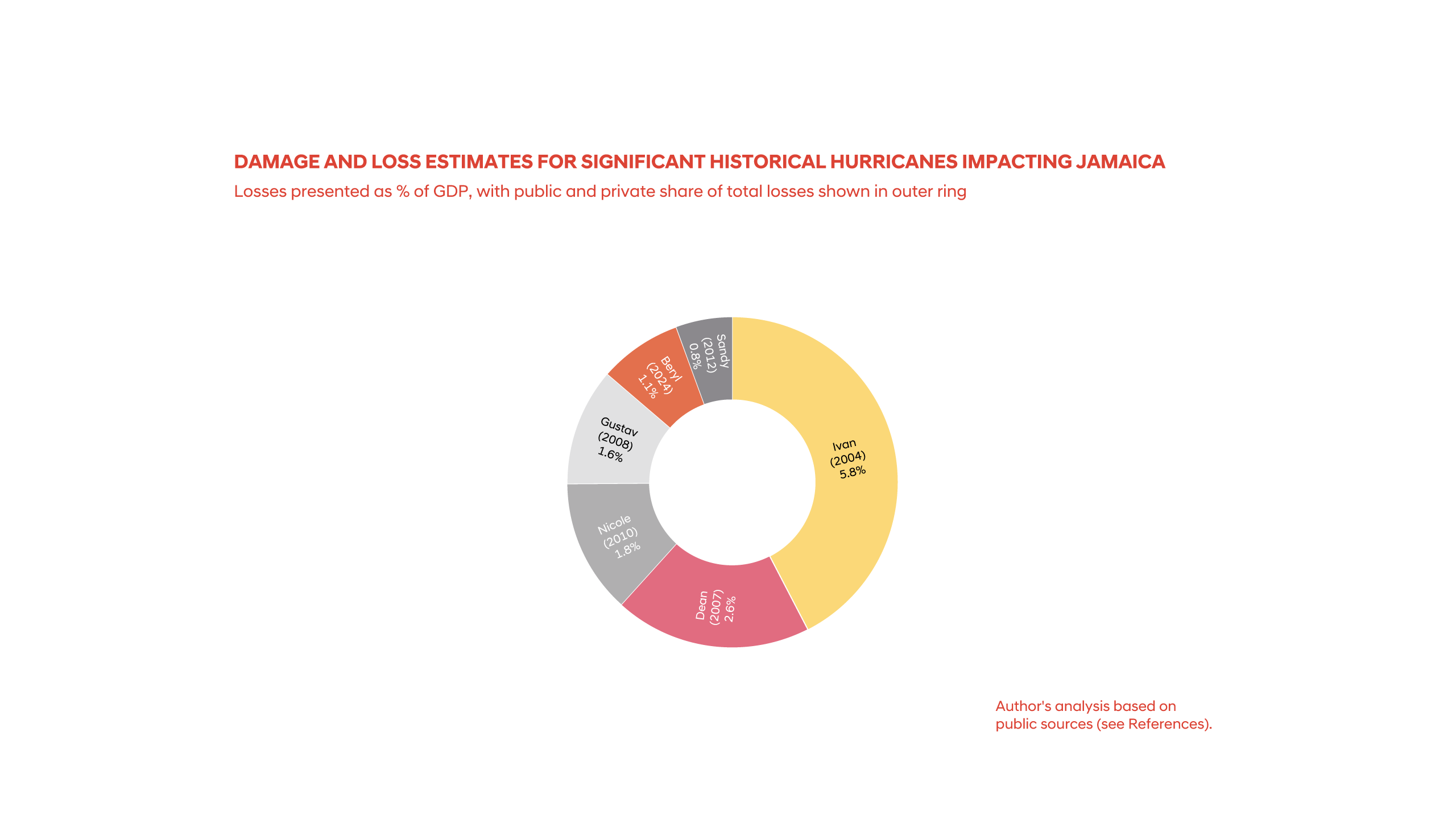

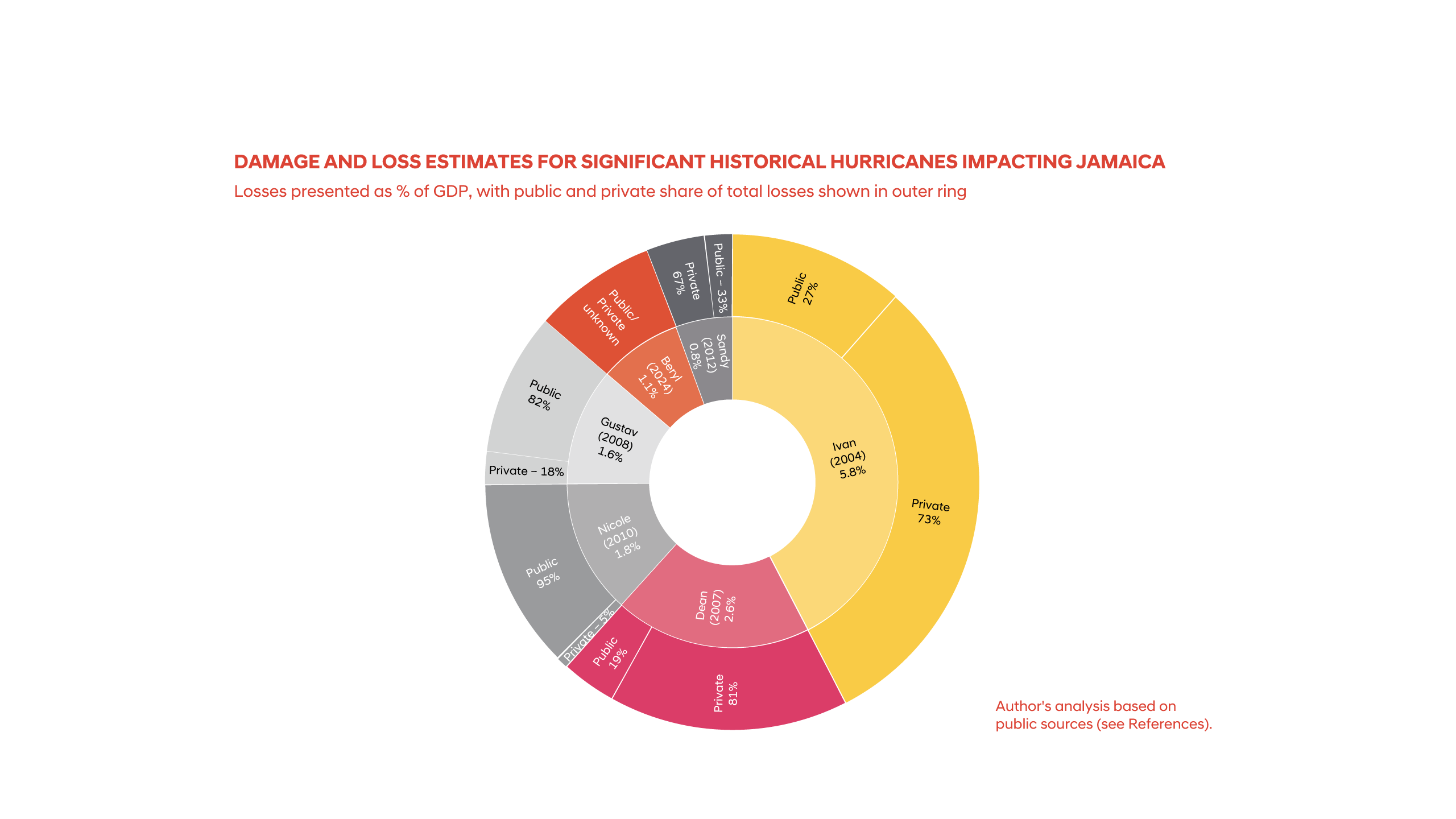

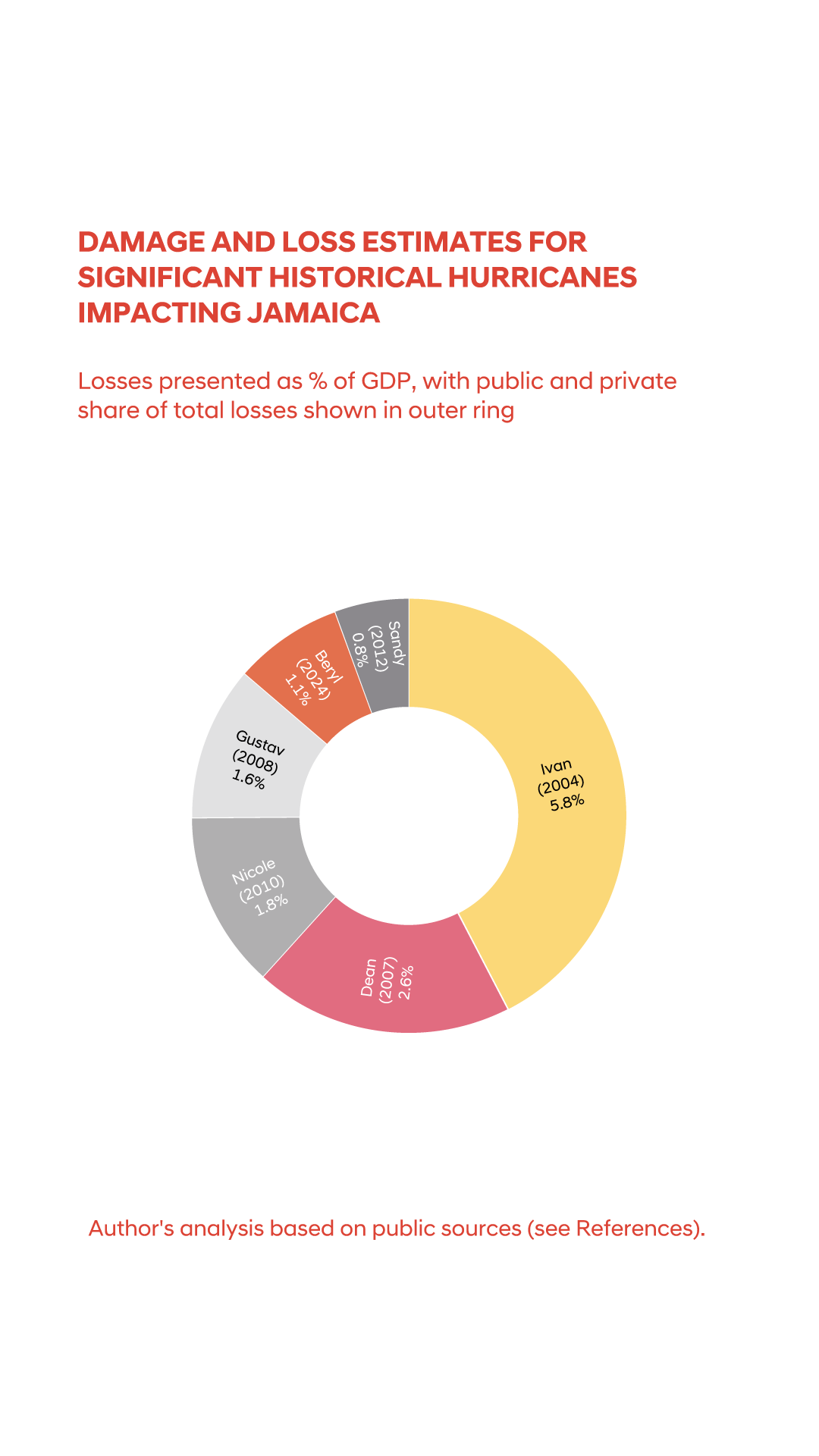

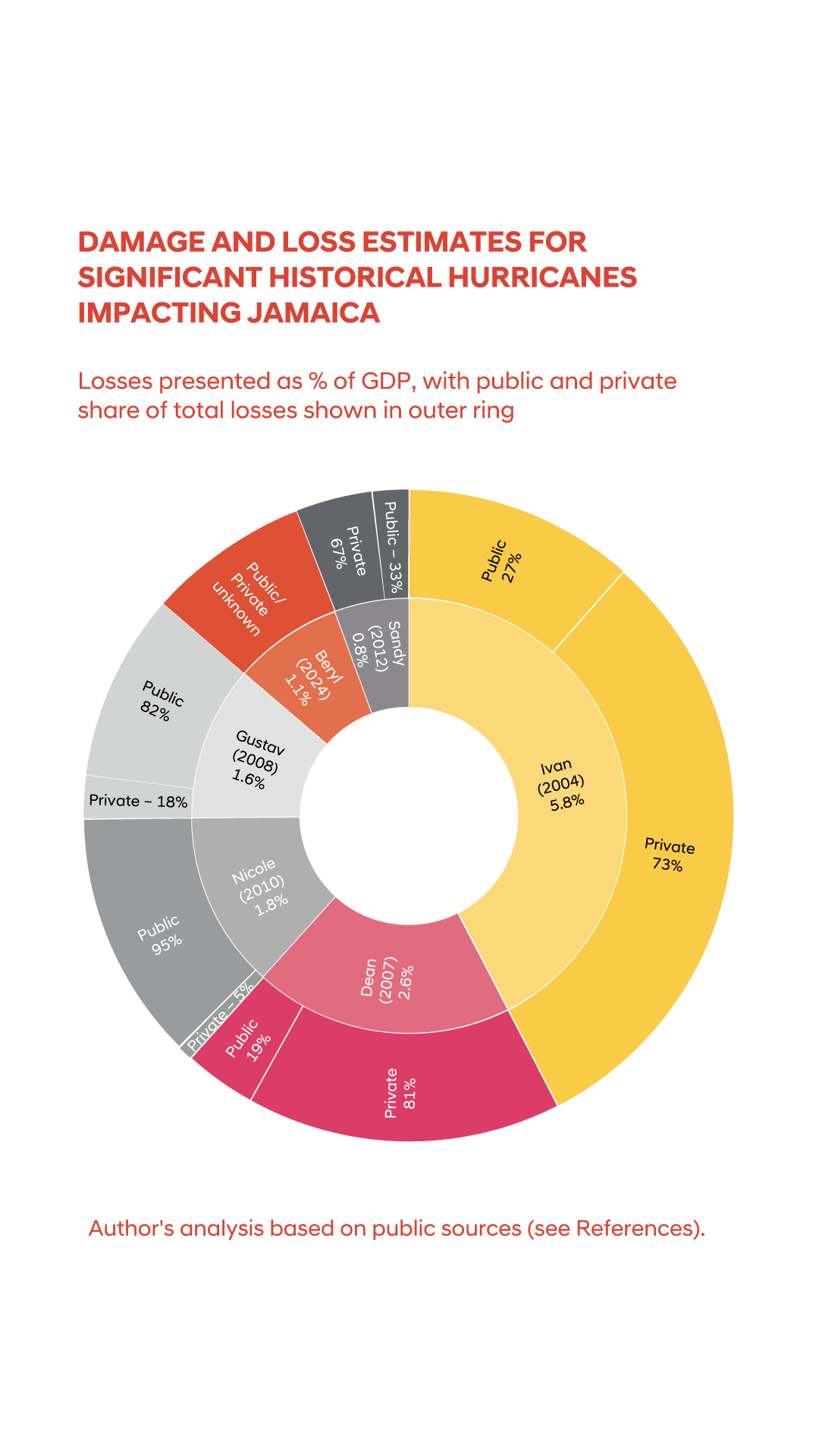

A review of historical hurricane losses highlights how the government’s share of total disaster costs can vary substantially between events. The graphic below shows that hurricanes Dean in 2007 and Nicole in 2010 caused losses of 2.6% and 1.8% of GDP at the time, but the public share of costs for Dean was only 19% compared with 95% for Nicole. Understanding the public share of total losses reflects the amount which could, in principle, be covered by pre-arranged financing. Differences in public versus privately owned costs are likely due to multiple factors, including whether infrastructure (mostly public) or productive sectors (mostly private) were most affected, as well as potential differences in the availability of relief and recovery funds or differences in how losses are accounted for. The exact ratio of public to privately owned costs relating to Beryl is not yet published, but based on previous experiences, we can assume that $200 million represents a conservative upper bound for the government’s costs, and the actual figure will be likely less than this. The analysis also highlights that Beryl is approximately the 5th most impactful storm in Jamaica over the past 25 years in terms of total costs as a portion of GDP.

Jamaica allocates US$85 million for ‘Hurricane Beryl Relief and Recovery’ in an interim budget update. A supplementary budget update in November provided additional detail on the government’s costs relating to Beryl. The first supplementary budget for 2024/2025 fiscal year included US$85 million budgeted explicitly for Hurricane Beryl Relief and Recovery. It is possible that some Beryl-related costs are not labelled explicitly in this budget, and additional recovery costs may be needed in future budgets, so this $85 million figure represents a lower bound estimate for the government’s response costs for Beryl.

From these sources, we can estimate that Beryl’s costs to the government were in the range of US$85-200 million.

Although Beryl caused damage and disruption in the south of Jamaica, it could clearly have been more costly had the hurricane made direct landfall or affected more populated areas with greater public infrastructure.

How did instruments in Jamaica's DRF strategy respond??

Nigel Clarke, Jamaica's finance minister. Credit: Hollie Adams/Bloomberg via Getty Images

Nigel Clarke, Jamaica's finance minister. Credit: Hollie Adams/Bloomberg via Getty Images

Jamaica’s disaster risk financing strategy has undergone significant evolution in recent years. Jamaica has formalised its strategy and expanded its risk financing toolkit within the wider context of a fiscal reform agenda from 2013, which saw Jamaica’s debt to GDP reduce from 144% to 72% from 2012 to 2023.

The fiscal reform agenda provides an important pretext for Jamaica’s 2021-2026 disaster risk financing strategy. When the government approved the development of a disaster risk financing strategy in 2018, the then Minister of Finance, Dr Nigel Clarke, commented that “the practice of shifting budgeted resources from planned activities is imprudent” and that the policy would “see Jamaica being more independent and responsive when disasters strike”. These rationales clearly recognise the risk to fiscal stability posed by unmanaged disasters and the value of strategically planning and paying for disasters in advance.

One of the key features of the DRF strategy is that Jamaica uses a risk layering approach. Risk layering is a concept in disaster risk financing, reflecting that different instruments are relatively more suitable and cost-effective for financing different types and severities of disaster impacts. The opportunities and challenges associated with choosing and combining instruments was analysed in detail in the Centre’s recent report Demystifying Pre-Arranged Financing for Governments. Layered disaster risk financing strategies effectively represent a combination of choices which a government has made about how to manage risk. In practice, different governments may make different choices when presented with the same options and technical analysis, so it is important to recognise that technical analyses about financially ‘optimal’ arrangements of instruments only form a part of the picture for decision-makers and broader practical and strategic considerations also feed into these decision-making processes.

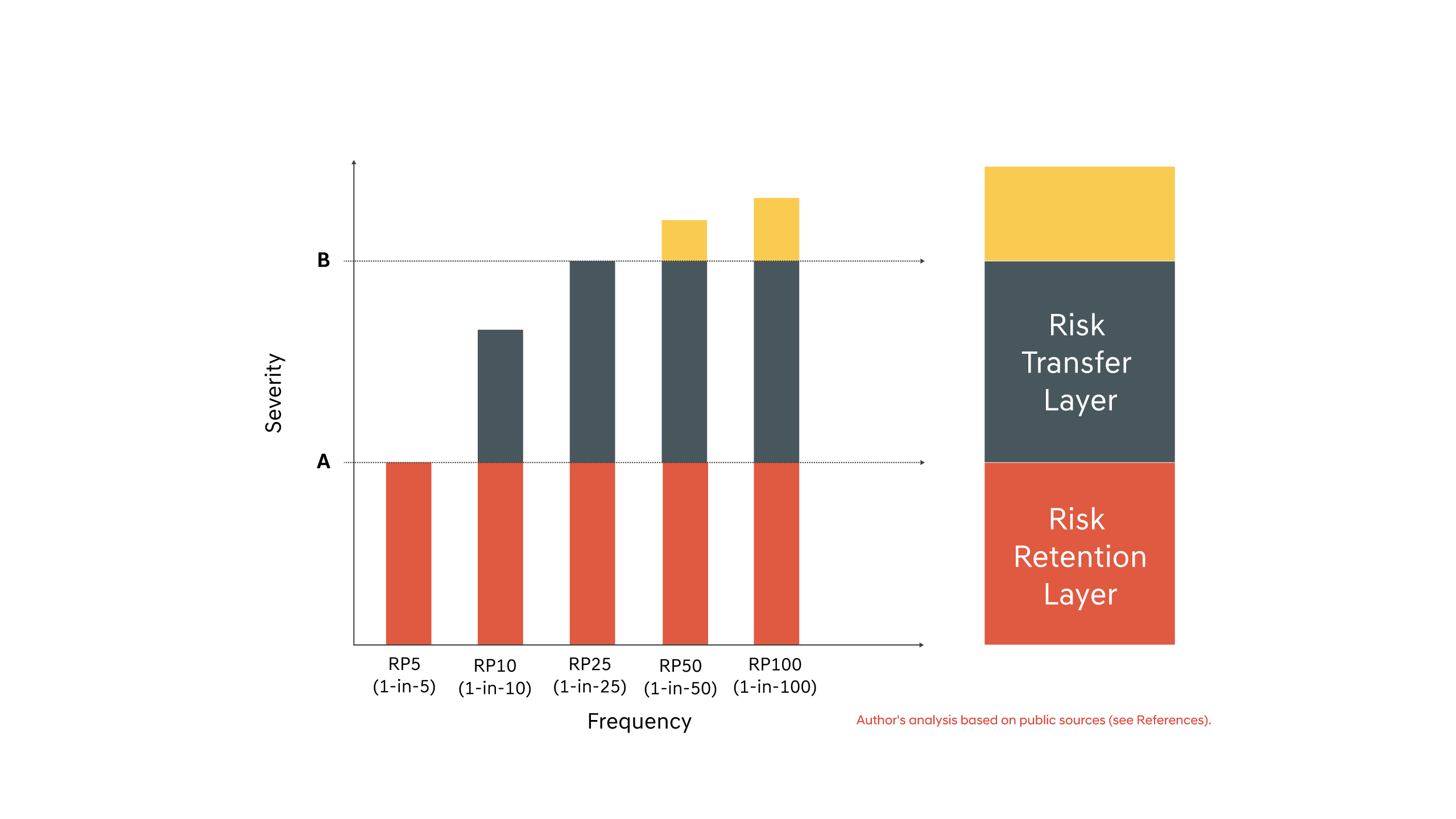

What is risk layering?

Risk layering is a concept in DRF that guides how pre-arranged financing instruments can be optimally combined to provide comprehensive and cost-effective financial protection across the full range of potential disaster impacts. Layering pre-arranged financing instruments so that different instruments kick in at different impact levels reflects the fact that that instruments vary in suitability and cost-effectiveness depending on how likely it is that funds will be needed.

There are two main categories of pre-arranged financing instruments:

- Risk retention instruments are mechanisms where the risk holder bears the financial responsibility for potential losses. This includes reserve funds (saved money set aside specifically for disasters) and contingent credit (pre-arranged loans that e can be quickly accessed when needed). These instruments are typically used as the first levels of protection, providing all or some of the funds for frequent, lower-impact disasters.

- Risk transfer instruments shift the financial responsibility for specific disaster losses to another party in exchange for a fee. Examples include parametric insurance (which pays out based on predefined disaster measurements) and catastrophe bonds (which transfer risk to investors). These instruments are generally better suited to providing additional funding for less frequent but more severe events, as their cost per dollar of coverage tends to be higher.

Risk layering for governments is similar to how households might use insurance for property or car insurance, with smaller damages being paid for out of savings (risk retention), and insurance stepping in to cover higher additional costs relating to more severe damage (risk transfer).

In ideal cases, catastrophe risk models are used to quantify the range of potential disaster costs to government, and the associated likelihood of different levels of funds being needed. Using this risk information alongside information on the costs and coverage of different financing instruments helps identify the optimal mix of instruments. This type of cost-benefit analysis can help to determine total crisis protection needs, and the levels of coverage and trigger thresholds of combinations of pre-arranged financing instruments.

However, cost optimisation is only part of picture. Practical and strategic factors also shape DRF strategies, for example:

- The types and sizes of disaster risks faced by a country.

- The feasibility and affordability of building and maintaining reserve funds.

- The availability of specific financing instruments within different country contexts.

- The suitability and reliability of triggers for different risk types and instrument options.

- The risk and instrument preferences of financial planners in government.

While technical analyses can help identify a financially ‘optimal’ risk layering structure, these practical considerations also influence instrument choices for DRF strategies

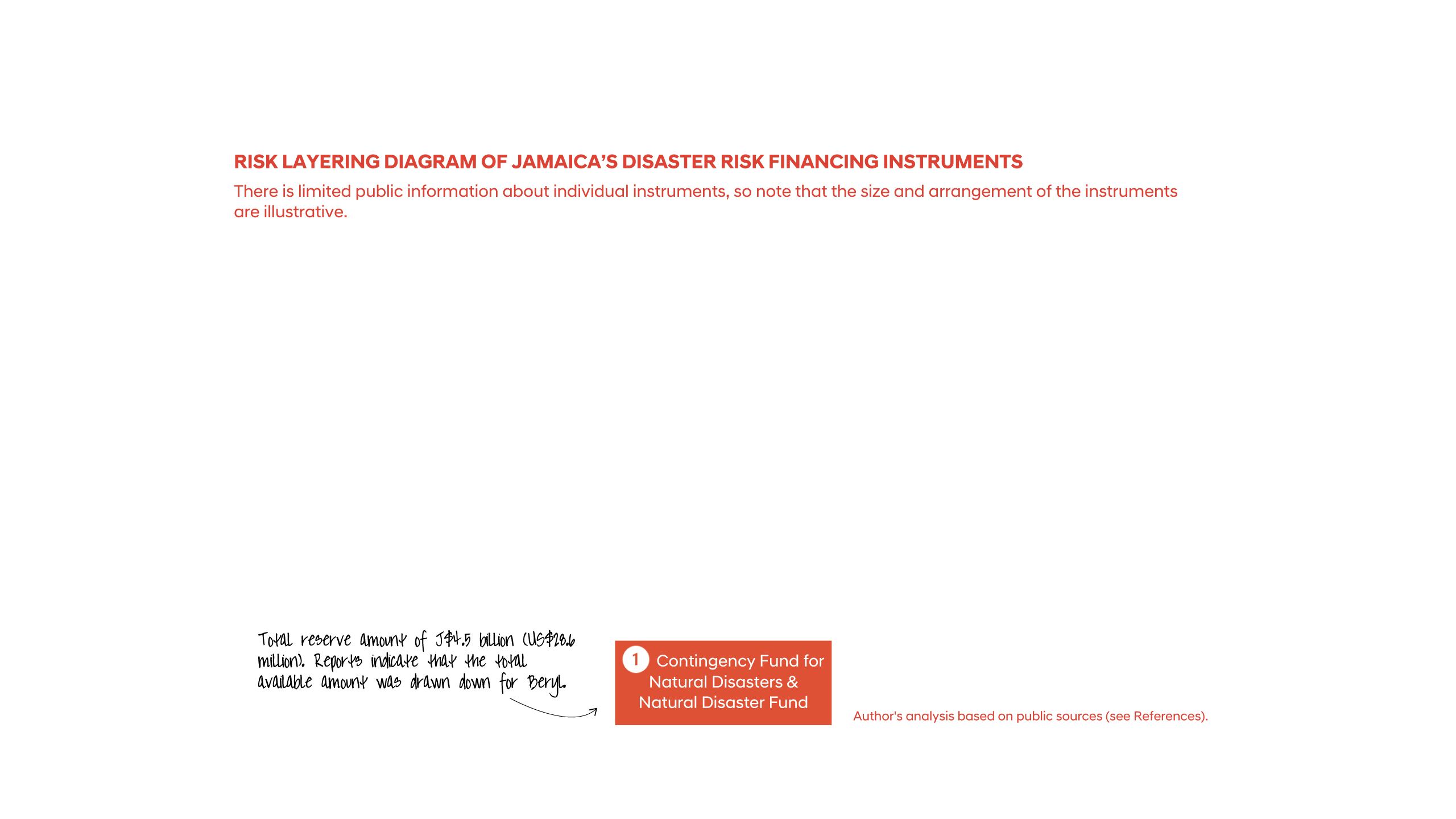

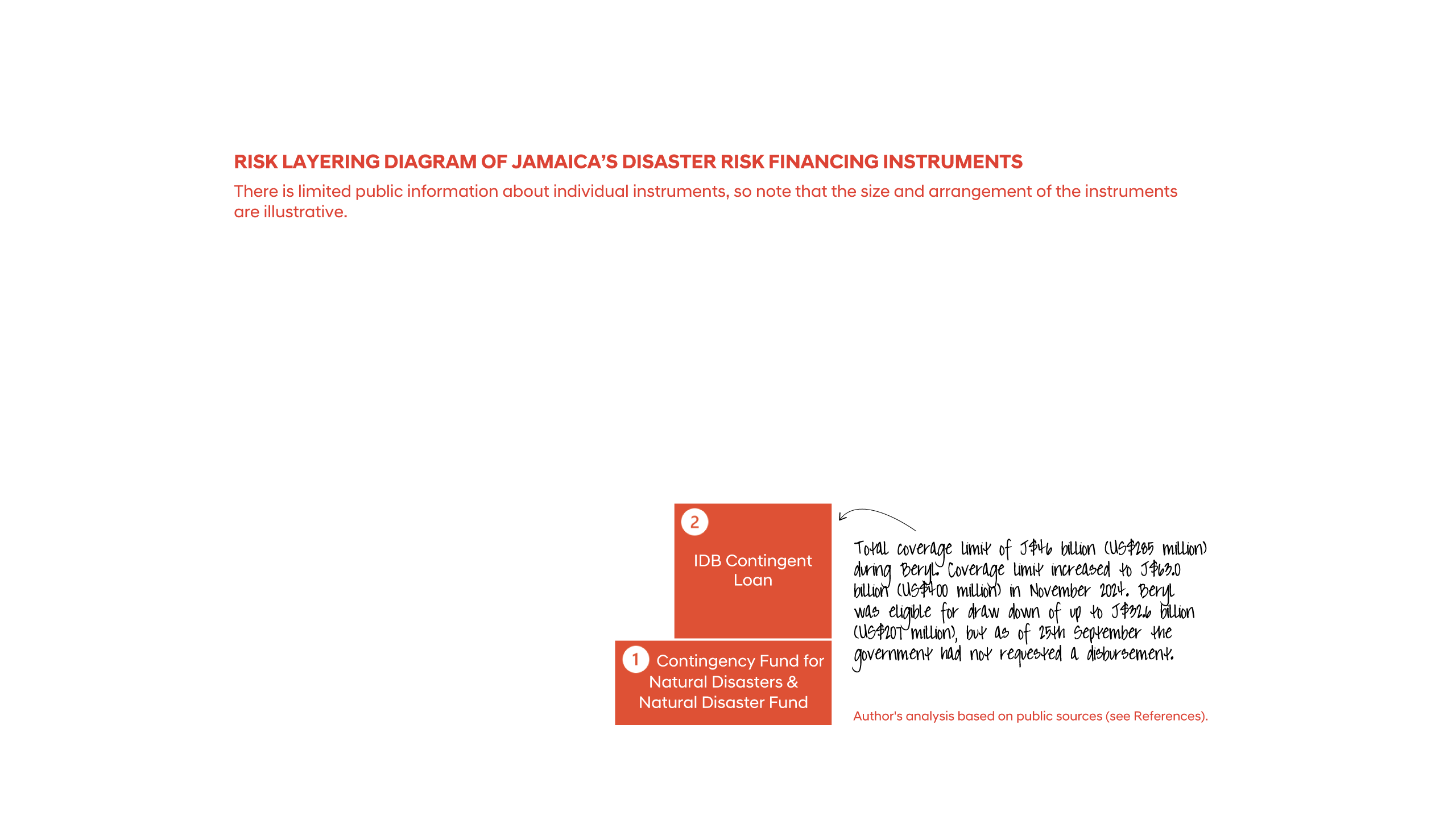

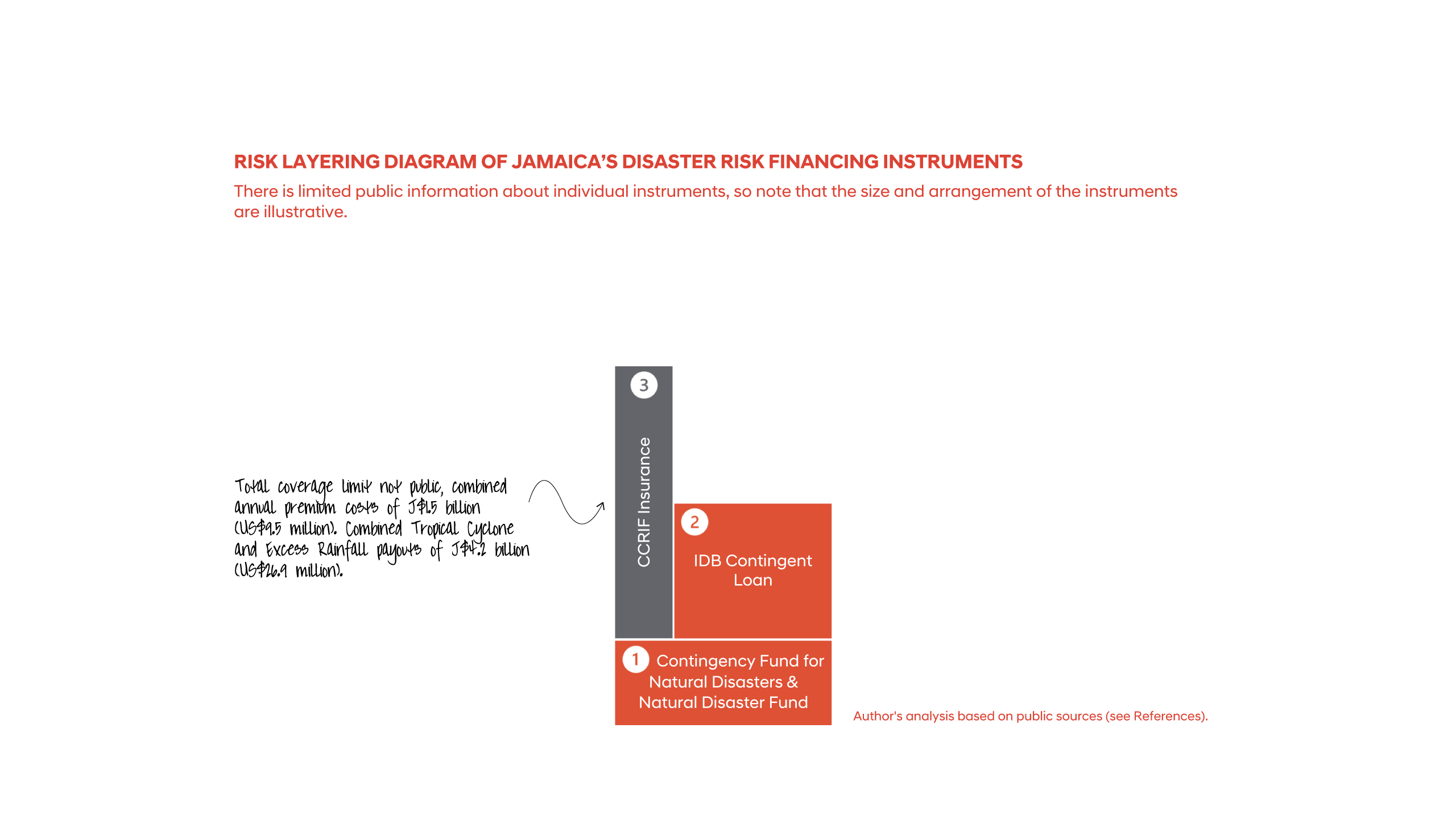

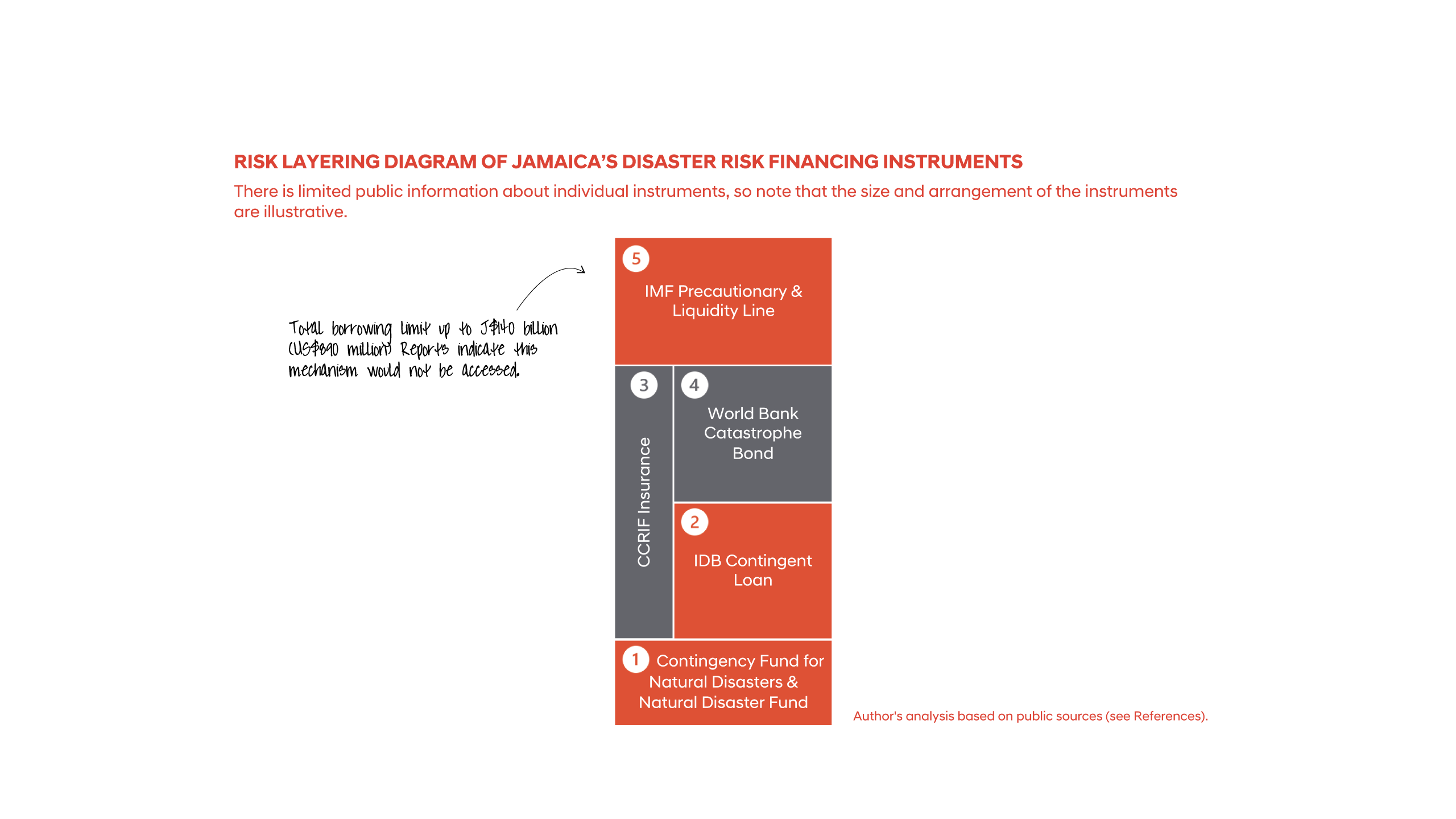

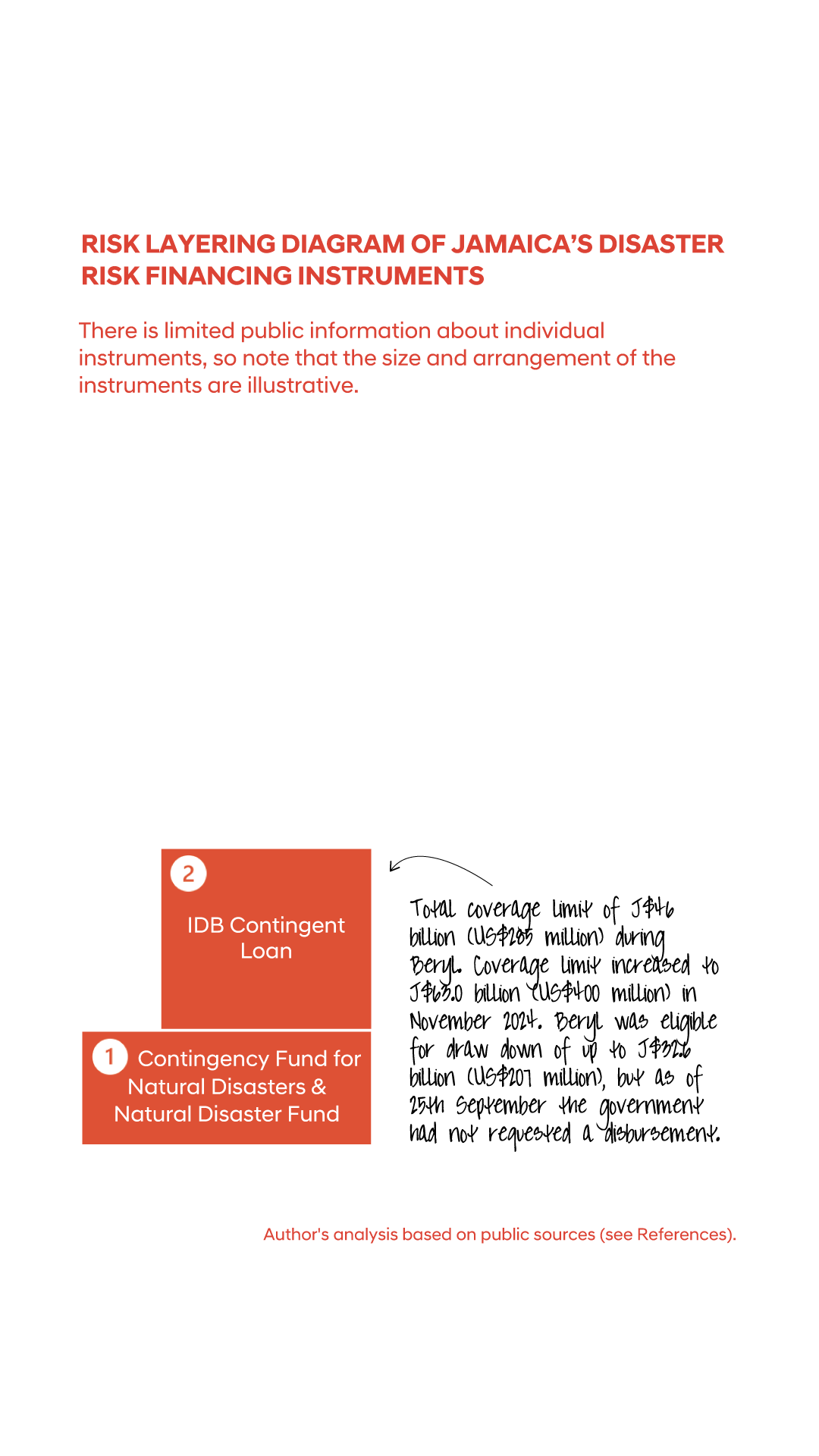

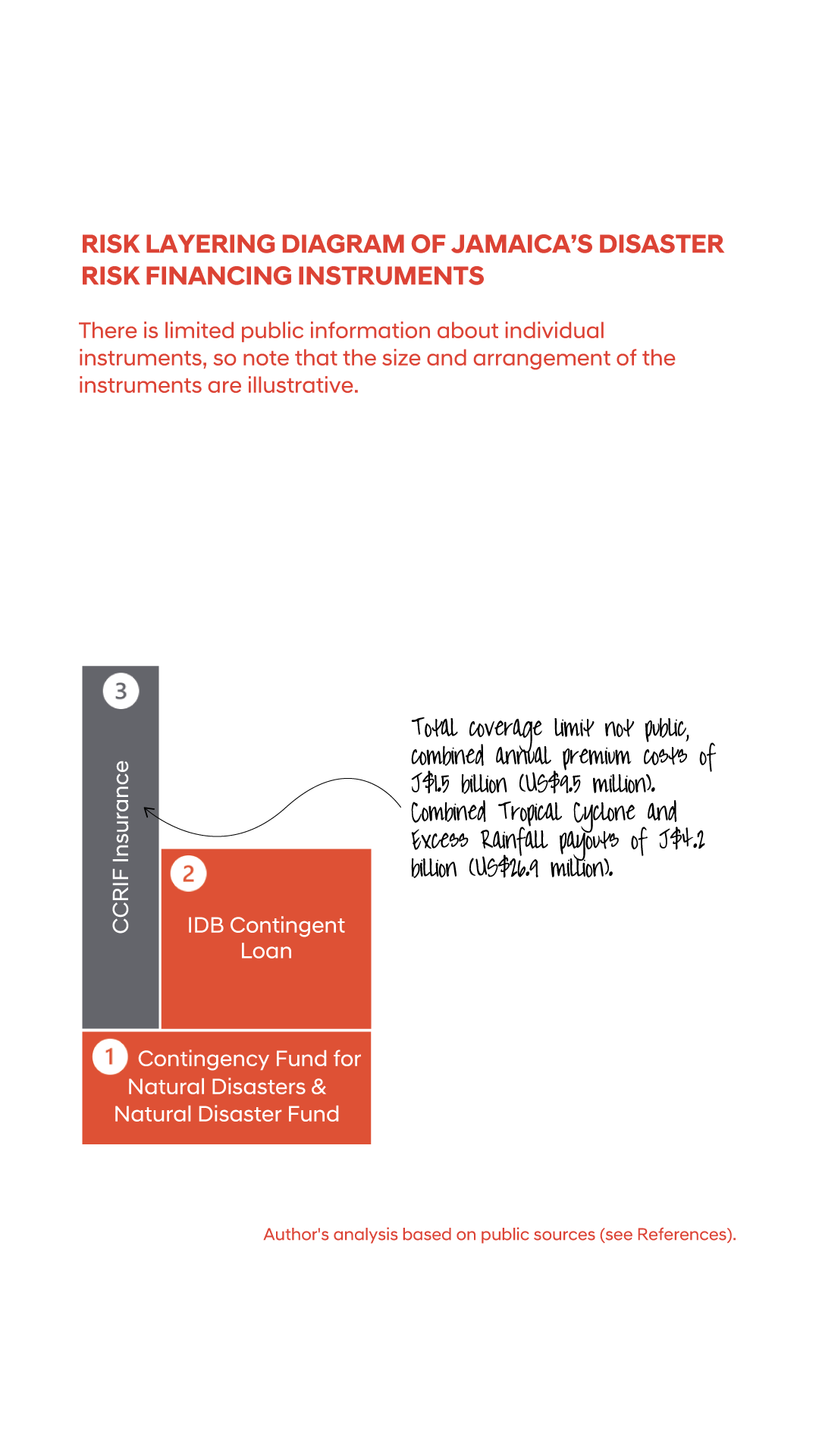

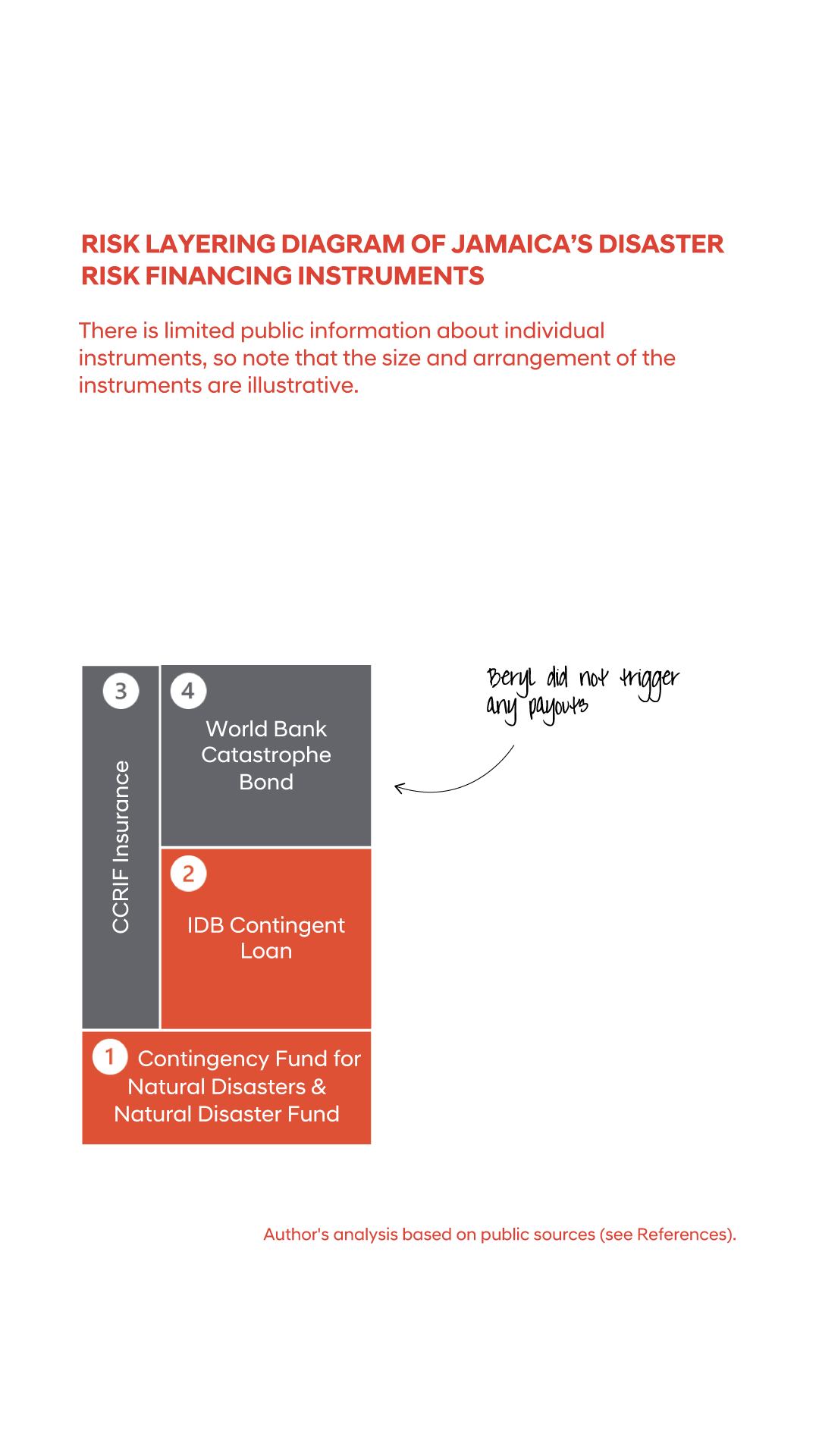

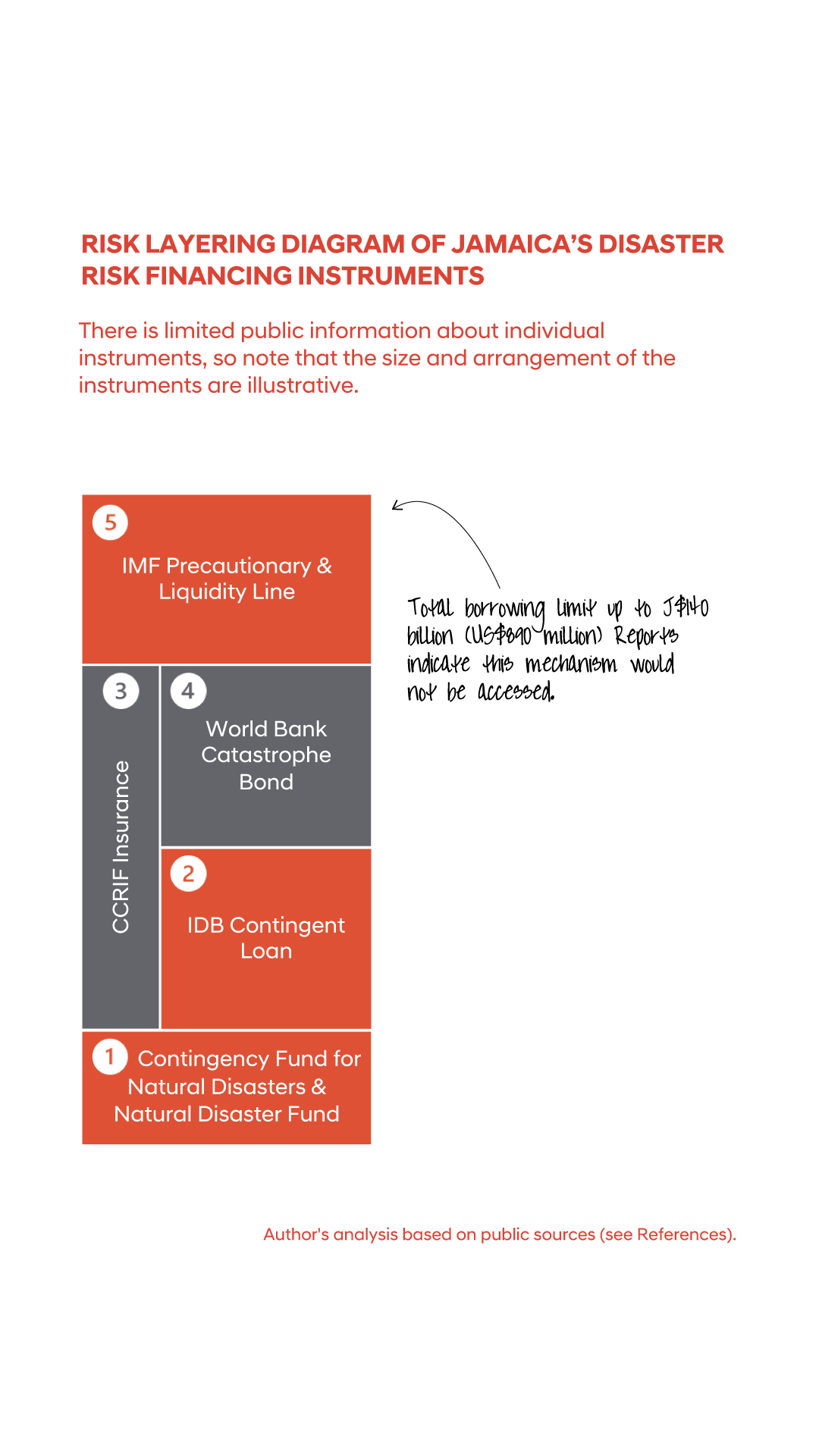

Jamaica’s layered disaster risk financing strategy currently consists of five main instruments. Three of these either provided, or are eligible to provide payments to support the government’s response to Beryl.

The combination of pre-arranged finances in Jamaica’s contingency funds, CCRIF’s automatic payout of $26.9 million and the additional US$207 million of headroom provided by the IDB contingent credit line indicate that the government had access to enough money to cover the US$85-200 million estimate of response costs.

Should Jamaica’s catastrophe bond have triggered?

Credit: Scott McIntyre/Bloomberg via Getty Images

Credit: Scott McIntyre/Bloomberg via Getty Images

In April 2024, Jamaica purchased its second World Bank-issued catastrophe (cat) bond, following the expiry of its first, which was issued in 2021. There were too main differences. Firstly, Jamaica paid the premiums for the 2024 issuance, whereas donors had covered the premium costs for the previous cat bond. Secondly, the market dynamics meant that the price charged for the 2024 issuance was around 60% higher than the first issuance. The fact that the cost of issuing the cat bond was so much higher probably contributed to the interest in the performance of the cat bond following Beryl.

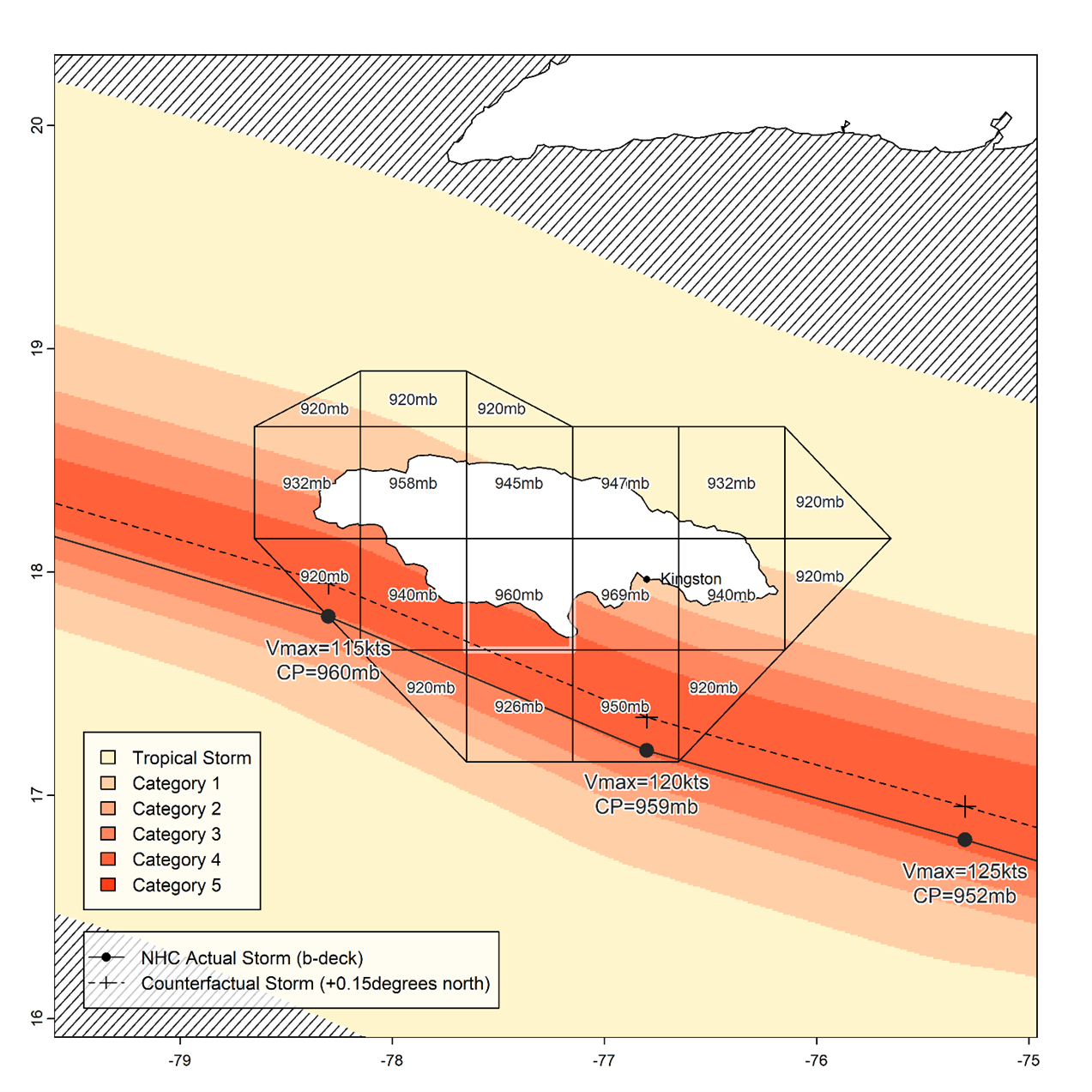

When Beryl approached Jamaica as a Category 5 storm, investors in Jamaica’s catastrophe bond monitored the National Hurricane Centre (NHC) event observation data to analyse if it would cause a parametric payout. As Beryl bypassed to the south of Jamaica, it was quickly apparent that its reported location and central pressure measurements were not sufficient to trigger a payout from the cat bond. However, the map below shows it was a close call – had the storm track been 15km further north, or if the reported central pressure was 10 millibars lower, the attachment threshold would have been breached, and the cat bond would have issued a payout of at least US$45 million.

Map of Hurricane Beryl's track as it interacted with the parametric cat-in-a-grid trigger mechanism of the catastrophe bond.

Map of Hurricane Beryl's track as it interacted with the parametric cat-in-a-grid trigger mechanism of the catastrophe bond.

This sort of near-miss scenario inevitably raises the question of whether there was a failure in the parametric trigger. Parametric trigger mechanisms are essentially a set of pre-defined calculations, which transform real-time data on the parameters of an event, such as track location and central pressure, into an index of financing needs. When they are designed well, parametric triggers can enable fast payments which align accurately with the financing needs of the responder. However, parametric trigger design relies on choices and trade-offs, and the impacts of crisis events and associated contingent liabilities are often more complex than can be captured using a pre-determined set of observations and calculations. The possibility that the parametric trigger doesn’t align with the policyholder’s needs or expectations is referred to as ‘basis risk’.

There are three reasons to suggest that this was not a basis risk event for Jamaica’s cat bond:

Beryl’s damage estimates don’t seem high enough to warrant a payout from the catastrophe bond layer. The catastrophe bond trigger is designed to issue payouts for events that cause losses expected to occur at a return period of 1-in-42 years (based on the modelled annual attachment probability of 2.34% of the cat bond). Based on PIOJ assessments of damage and loss as a function of GDP, Beryl is Jamaica’s fifth most impactful storm of the past 25 years, so has a historical return probability of 1-in-5 over this period. This basic analysis does not account for improvements in vulnerability or changes in exposure through time and is not based on enough data to get an accurate view of the actual return period estimate of Beryl’s severity. However, it suggests Beryl’s severity was lower than the minimum threshold that the catastrophe bond was designed to protect against. In other words, since the historical return period of Beryl’s losses is so much lower than the modelled attachment period of the catastrophe bond, even with conservative assumptions, it looks like Beryl wasn’t severe enough to warrant a payout from the catastrophe bond layer.

The public messaging from Jamaica’s Ministry of Finance does not indicate they expected a cat bond payout following Beryl. The Ministry of Finance stressed in public communications following Beryl that Jamaica intentionally uses a multi-layered set of financial instruments, indicating that while “… it is neither expected nor designed that all storms will trigger all instruments, the idea is that we should always be able to access resources from some instruments for every storm”. This external communication clearly doesn’t reflect the full range of views on the catastrophe bond from within the government, and it would, of course, have been preferable for Jamaica had the cat bond delivered a fast return on investment, but in the sense that basis risk reflects the difference between the triggered outcome and the expectation of the policy holder, these sorts of comments suggest that at least from the perspective of the government, Beryl does not represent a basis risk event for the catastrophe bond.

The amount of pre-arranged financing available from other instruments in Jamaica’s DRF strategy was greater than the higher estimates of total damage and loss. Even without the cat bond triggering, the funding available through other instruments in Jamaica’s DRF strategy was more than sufficient to cover the US$85 million of Beryl-related costs in the supplementary budget. The triggered instruments include US$207 million the IDB contingent credit line, which was eligible for disbursement, but appears not to have been drawn down by Jamaica. The fact that the DRF strategy provided access to enough pre-arranged funding even without the cat bond triggering also suggests that collectively, Jamaica’s DRF strategy performed well in response to Beryl. On its own, the fact that other instruments triggered doesn’t confirm that this wasn’t a basis risk event for the cat bond, but collectively, it does suggest that Jamaica’s risk financing strategy worked as it needed to.

This view that the cat bond trigger performed well contrasts with some issues raised with the cat bond in other public commentaries, including an assessment by the V20 group, which concludes that Beryl highlights flaws in the use of sovereign catastrophe bonds, which should be corrected to allow greater flexibility for countries.

Analysing instrument performance in real-time is an important check and balance to make sure things are working as designed. However, it is important to distinguish any real-time analysis of triggers from the wider question of the role of cat bonds in sovereign risk financing strategies, or specifically whether Jamaica could or should have chosen to spend its premium for cat bonds on other pre-arranged financing instruments. Ultimately, Jamaica made a choice to buy the cat bond to provide financing for lower likelihood, higher severity events, and at least for Beryl it has worked as it was designed.

There are three reasons to suggest that the parametric trigger did indeed align with the policyholder’s needs and expectations.

A strategy as the sum of its parts

Credit: Jewel Samadafp via Getty Images

Credit: Jewel Samadafp via Getty Images

This analysis on Beryl’s estimated impacts and costs, the response of Jamaica’s financing strategy, and review of the cat bond trigger are open to different interpretations. However, collectively they suggest that Jamaica’s risk financing strategy worked well given the level of government losses, and Beryl does not look like a basis risk event for the catastrophe bond.

Each disaster presents an opportunity for learning, and Jamaica and other countries can use this experience with Beryl to inform choices about how to plan and pre-arrange financing for future shocks. The high-level view of Jamaica’s disaster risk financing response for Beryl is largely a positive one, which shows how strategically arranged combinations of instruments can work together to provide predictable and fast funds to support disaster response and recovery.

Different combinations of instruments are more or less applicable in different situations and countries should, of course, aim to make instrument choices based on their own contexts rather than replicating Jamaica’s strategy.

However, one aspect of Jamaica’s approach which is relevant everywhere is their active and strategic engagement of pre-arranged financing to address their disaster risk so that costs for events like Beryl are managed ahead of time rather than in the heat of the crisis.

References

- Planning Institute of Jamaica (PIOJ). (2024). The Planning Institute of Jamaica’s Review of Economic Performance, July–September 2024: Media Brief (November 20, 2024). Retrieved from https://www.pioj.gov.jm/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/DGs-QPB-29_2-Speaking-Notes.pdf.

- Bloomberg News. (2024, July 3). Hurricane Beryl Tests Jamaica’s $1.6 Billion Disaster Safety Net. Retrieved from https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2024-07-03/hurricane-beryl-tests-jamaica-s-1-6-billion-disaster-safety-net.

- Bloomberg News. (2024, July 5). Catastrophe Bond Investors Dodge Losses After Beryl Hits Jamaica. Retrieved from https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2024-07-05/catastrophe-bond-investors-dodge-losses-after-beryl-hits-jamaica.

- Global Facility for Disaster Reduction and Recovery (GFDRR). (2024, July 26). Global Rapid Post-Disaster Damage Estimation (GRADE) Report: Hurricane Beryl 2024 – Saint Vincent and the Grenadines. Retrieved from https://www.gfdrr.org/en/publication/grade-2024-svg.

- Global Facility for Disaster Reduction and Recovery (GFDRR). (2024, August 1). Global Rapid Post-Disaster Damage Estimation (GRADE) Report: Hurricane Beryl 2024 – Grenada. Retrieved from https://www.gfdrr.org/en/publication/global-rapid-post-disaster-damage-estimation-grade-report-hurricane-beryl-2024-grenada.

- Planning Institute of Jamaica (PIOJ). (2024). Damage and Loss Reports. Retrieved from https://www.pioj.gov.jm/?s=damage+and+loss.

- Ministry of Finance and the Public Service (MOFPS), Jamaica. (2024). First Supplementary Estimates 2024/2025. Retrieved from https://www.mof.gov.jm/wp-content/uploads/2024-2025-1st-Supplementary-Estimates_AS-PASSED.pdf.

- Arslanalp, S., Eichengreen, B., & Henry, P.B. (2024). Sustained Debt Reduction: The Jamaica Exception. National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER), Working Paper No. 32465. Retrieved from https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w32465/w32465.pdf.

- Ministry of Finance and the Public Service (MOFPS), Jamaica. (2024). National Natural Disaster Risk Financing Policy (NNDRFP). Retrieved from https://www.mof.gov.jm/media/national-natural-disaster-risk-financing-policy-nndrfp/.

- Jamaica Gleaner. (2018, November 7). Cabinet Approves Plan to Create Disaster Risk Policy. Retrieved from https://jamaica-gleaner.com/article/news/20181107/updated-cabinet-approves-plan-create-disaster-risk-policy.

- Mustapha, S., & Benson, C. (2024). Demystifying Pre-Arranged Financing for Governments: A Stocktake of Financial Instruments from International Financial Institutions. Centre for Disaster Protection, London.

- Jamaica Information Service (JIS). (2024). Update on the Disaster Risk Financing Instruments from the Minister of Finance and the Public Service. Retrieved from https://jis.gov.jm/update-on-the-disaster-risk-financing-instruments-from-the-minister-of-finance-and-the-public-service/.

- Inter-American Development Bank (IDB). (2024). Contingent Loan for Natural Disaster Emergencies (JA-O0004). Retrieved from https://www.iadb.org/en/project/JA-O0004.

- Inter-American Development Bank (IDB). (2024). Contingent Loan for Natural Disaster and Public Health Emergencies (JA-O0016). Retrieved from https://www.iadb.org/en/project/JA-O0016.

- Evans, S. (2024, July 4). Hurricane Beryl Not Expected to Trigger Jamaica Cat Bond Loss, Plenum Confirms. Artemis. Retrieved from https://www.artemis.bm/news/hurricane-beryl-not-expected-to-trigger-jamaica-cat-bond-loss-plenum-confirms/.

- International Monetary Fund (IMF), Western Hemisphere Department. (2023, March 7). Jamaica: Request for an Arrangement Under the Precautionary Liquidity Line and Request for an Arrangement Under the Resilience and Sustainability Facility - Press Release; Staff Report; Staff Statement; and Statement by the Executive Director for Jamaica. Retrieved from https://www.elibrary.imf.org/view/journals/002/2023/105/article-A001-en.xml.

- Jamaica Information Service (JIS). (2024). Gov’t Remains Confident That Jamaica Will Recover from Hurricane Beryl. Retrieved from https://jis.gov.jm/govt-remains-confident-that-jamaica-will-recover-from-hurricane-beryl/.

- Evans, S. (2024, July 3). Hurricane Beryl Forecast to Pass Just South of Jamaica, Cat Bond Still on Watch. Artemis. Retrieved from https://www.artemis.bm/news/hurricane-beryl-forecast-path-jamaica-catastrophe-bond-on-watch/.

- IBRD CAR Jamaica. (2024). IBRD CAR Jamaica 2024. Retrieved from https://www.artemis.bm/deal-directory/ibrd-car-jamaica-2024/.

- Ahmed, S.J., & Rambarran, J. (2024, July 22). Insights: Financial Protection – The World Bank Should Course Correct for More Flexible Cat Bond Trigger Conditions in the Wake of Jamaica’s Experience with Hurricane Beryl. Climate Vulnerable Forum. Retrieved from https://cvfv20.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/Insights-Financial-Protection.pdf